Norway’s coastal communities and ocean industries want stricter regulations and greater investment in becoming more sustainable. Governments around the world have acted swiftly to suppress the coronavirus – a similar coordinated effort would be an effective tool to combat the climate changes we are facing.

In 2019, the Centre for the Ocean and the Arctic travelled the coast of Norway, from Longyearbyen in the High North to the southern capital of Oslo. The purpose of our journey was to listen to coastal communities and report back their visions for a sustainable ocean economy to the Norwegian government.

By organizing our journey as a string of public debates, we met with politicians, businesses, finance, environmental activists, academics, and student – all in all a great variety of people, who yet had one goal in common: To scale up the pace of ‘the green shift’ through greater cooperation, investments, as well as stronger state regulations. However, to do so, we were told, Norway’s politicians must take responsibility and lead the way.

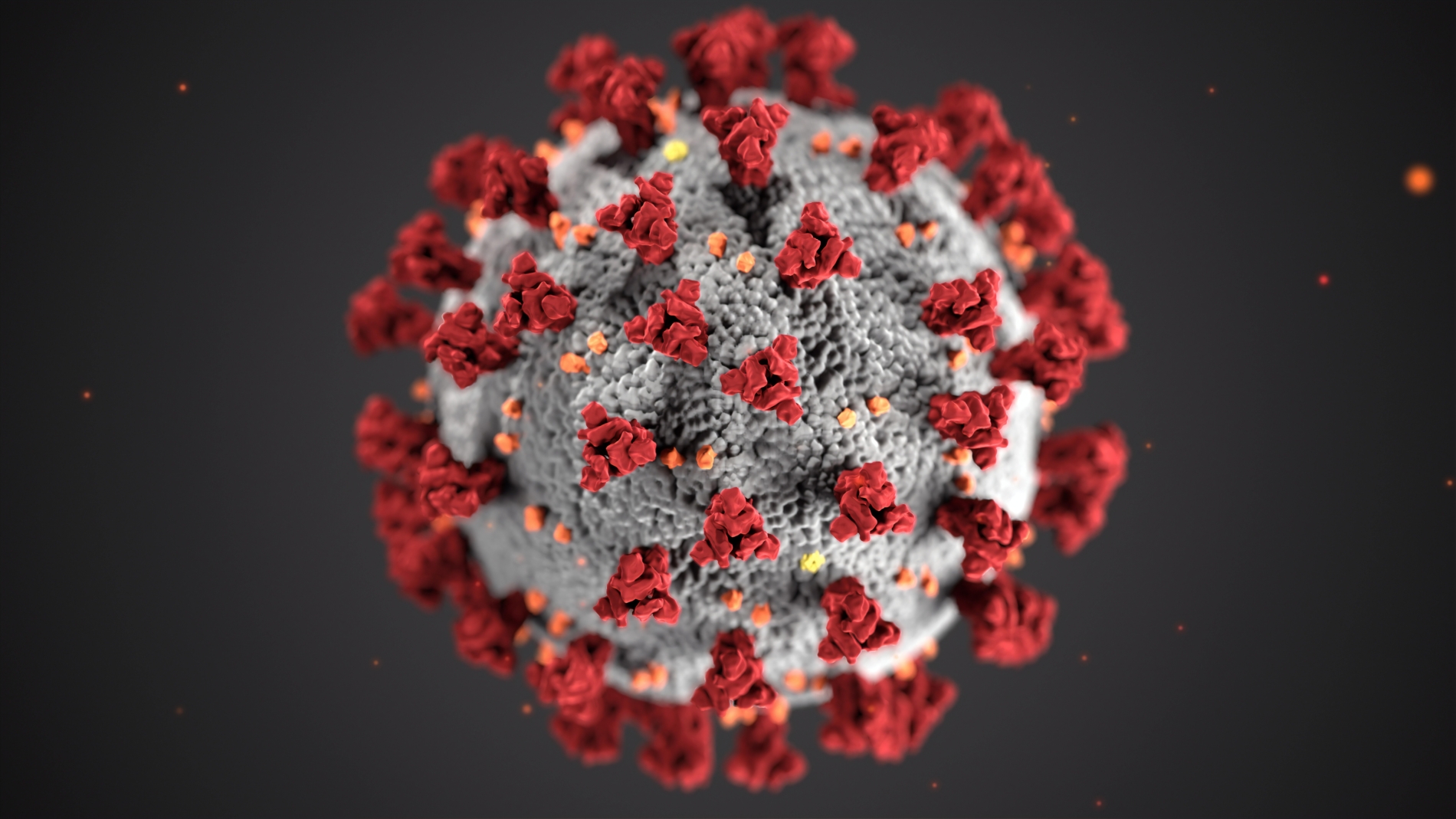

Little did we then know that the coronavirus pandemic would hit a few months later, showing us that governments are, in fact, very capable of doing so.

Replacing houses in Svalbard

An initial stopover in the archipelago Svalbard was a fitting place to begin our discussions about the consequences of climate change and adaptation strategies. Svalbard is among the fastest-warming places on Earth, which its residents feel every day.

Since 1971, the winters here have become seven degrees warmer, way beyond the two-degree target set out in the Paris Agreement. While climate change used to be something affecting nature and wildlife, it now severely impacts the whole of society.

Over the past few years, new practices for building on (thawing) permafrost have been developed, many houses in Longyearbyen are being replaced and people are evacuated on a frequent basis due to the increased risk of snow avalanches. In 2017, lives were lost for this very reason. Indeed, there is no doubt that the increased risks of living in Svalbard calls for great caution.

Sustainability as competitive advantage

However, as we continued onto the Norwegian mainland, we soon learned that the issues of climate change also have a firm footing along the whole of Norway’s coast, and importantly, that our ocean industries are among the greatest advocates for finding and adopting climate change solutions.

Time and again, we were told by ocean businesses how sustainability is already becoming a competitive advantage. Many are now taking steps to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions, and to develop more climate- and environmental-friendly operations.

Deep Vision, which has developed a subsea vision system for identifying and measuring fish, is but one example. By attaching a camera to a trawl, the system optimizes the catch composition to the allowed quotas and dramatically reduces bycatch, being both more sustainable and profitable for the fishermen.

Aker Solutions is another example. The company is now using its experience from offshore petroleum projects to develop offshore wind projects. The trend we are witnessing is further strengthened by financial institutions, which are increasingly using sustainability as a criterion for selecting investment projects and issuing loans.

That said, many small businesses are still struggling to put the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals into practical local solutions.

The tourism industry wants stricter regulation

Moving from the general to the more sector-specific, we were surprised to hear the tourism industry ask for stricter regulations on its own activities. Tourism is a fast-growing industry closely related to recreation at sea and along the coast.

However, the necessary restrictions have not been able to keep up with this development. For one thing, tourism is an industry with a large climate footprint, not least because foreign tourists often travel far – usually by plain – to experience Norway.

Virke tourism association, a part of the Federation of Norwegian Enterprise, was among the actors we met that challenged the authorities to impose tough but achievable climate requirements for the industry.

Others pointed out a lack in search and rescue capacity, making further expansion of the industry irresponsible. This is especially true for cruise traffic in the Arctic, where the number of passengers has increased considerably, distances are great, and the weather inhospitable. An accident, were it to occur, could be fatal for humans, animals, and nature. In order to reduce risk, several actors from the tourism industry suggested to limit the size of cruise ships and the number of passengers. Further, a ban on use of heavy oil can lead to less damage in the event of an accident.

Petroleum industry to go green

Also, within Norway’s largest industry—petroleum—the desire to change course has been evident. However, what is not that evident, according to industry itself, is how. On the one hand, a restructuring of the industry must ensure profits. At the same time new jobs must be created for the hundreds of thousands working within the petroleum sector.

To safeguard such a development, SAFE, the main trade union for personnel working in the energy sector, suggested using the Norwegian fiscal rule as an instrument. The fiscal rule says that transfers from the Government Pension Fund Global to the central government budget shall follow the expected real return on the fund. At the inception of the fiscal rule in 2001, the expected real rate of return was set at 4 percent, but in 2017 the estimate was reduced to 3 percent. According to SAFE, the “excess” percent should be earmarked to finance research and innovation, utilizing the competence and knowledge developed throughout the Norwegian oil adventure in other ocean businesses, such as offshore wind and fish farming. Such measures can help create green jobs, new revenues, as well as adaptability and a positive shift in attitudes.

A corona-effect?

All in all, our journey revealed a clear consensus that our coastal societies—and our ocean industries—are ready to change, and that a reorientation of business and lifestyles is necessary. However, what we need more than anything is political will, which many stakeholders agreed has been insufficient.

Then in March the coronavirus pandemic manifested in Norway. In a matter of days, the entire country shut down, as the government introduced the strictest and most invasive measures since World War II. Given our politicians firm reaction, it now seems timely to wonder if the same impressive determination could be used to tackle the climate crisis, which after all represents an even more serious threat than the current pandemic.

Climate change occurs more slowly, and the consequences become more severe the longer it takes before substantial action is taken. Hopefully, the current painful reminder of how vulnerable societies are can inspire us to take more proactive steps to address this critical issue. And perhaps the Arctic – a region severely affected by climate change, but also home to many of our ocean industries – can lead the way with new innovative solutions.